Delve into Chromosome 10: Exploring Stress Hormones and Their Genetic Foundations

After delving into chromosome 6 and chromosome 11 in previous titles, our focus now shifts to chromosome 10. Specifically, we will explore how the brain and body processes respond to stress.

Delving into the CYP17A1 Gene

My impetus for composing this chapter stemmed from the realization that our physical state cannot be deceived when our minds are in disarray. This realization propelled me to acquaint myself with the CYP17A1 gene, situated on chromosome 10. The CYP17A1 gene is responsible for encoding members of the cytochrome P450 enzyme family. Like its counterparts, CYP17A1 plays a crucial role in synthesizing steroid hormones. This gene enables the conversion of cholesterol into cortisol, testosterone, and estradiol — essential steroid hormones. This synthesis process is vital for regulating the body’s salt and water balance, as well as for managing glucocorticoids, which help maintain blood sugar levels and regulate the body’s response to stress.

Cholesterol itself stands as a vital component within the body, positioned at the core of a biochemical and genetic system that orchestrates the functions of the entire organism. Five pivotal hormones — progesterone, aldosterone, cortisol, testosterone, and estradiol — are derived from cholesterol. Without the presence of the cytochrome P450 enzyme, cholesterol can only produce progesterone and corticosterone. Thus, besides its role in stress regulation, the absence of an active copy of this gene can result in significant impacts. For instance, in individuals genetically assigned as male, the deficiency in this gene impedes the synthesis of other sex hormones, leading to a delay in puberty and potentially manifesting physical traits resembling those of females.

So, what is the relationship between cortisol and stress?

The body primarily synthesizes cholesterol from the sugars we consume. Subsequently, the CYP17A1 gene transforms cholesterol, producing essential hormones, including cortisol. Cortisol, a hormone utilized across virtually all bodily systems, impacts the integration of body and mind by influencing brain configuration. Elevated cortisol levels are strongly correlated with diminished memory performance in both normal and pathological cognitive aging. Consequently, heightened cortisol levels are believed to heighten the brain’s vulnerability to the impacts of internal and external disorders. As such, cortisol may contribute to the onset and progression of age-related cognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Stress serves as one of the primary triggers for cortisol secretion within the body. Stress can be categorized into two main types: short-term stress and long-term stress.

Short-term stress triggers an immediate surge in epinephrine and norepinephrine levels. Epinephrine and norepinephrine accelerate heart rate and induce a sensation of coldness in the extremities. For instance, when confronted with the stress of facing a school exam, these hormones surge to prepare the body for a fight-or-flight response in emergency scenarios. Once the threat dissipates, hormone levels revert to their baseline, and bodily functions return to normalcy.

In contrast, during long-term stress, the activation of various pathways takes longer, resulting in a gradual yet sustained increase in cortisol levels, which ultimately disrupts the immune system. Typically, the normal cortisol range in a blood sample collected at 8 am is between 5 to 25 mcg/dL.

The mechanism of excess cortisol in disrupting the immune system

One effect of elevated cortisol levels is a reduction in the activity, quantity, and lifespan of lymphocytes, commonly known as white blood cells. Lymphocytes play a crucial role in defending the body against viral or bacterial infections. In adults, the normal lymphocyte level ranges from 1,000 to 4,800 cells/microliter of blood. Consequently, increased cortisol levels participate in activating a TCF gene, enabling TCF to produce its own proteins. These proteins are responsible for suppressing the expression of another protein called Interleukin-2.

What happens if the interleukin-2 protein isn’t expressed? Interleukin-2 serves as a chemical signal that heightens the vigilance of white blood cells, particularly against aggressive pathogens. When cortisol obstructs the alertness of white blood cells, the body becomes more vulnerable to diseases. Consequently, individuals experiencing stress, characterized by heightened cortisol levels, are more prone to viral infections and illnesses.

Amidst all the elucidations provided earlier, an intriguing question arises: Who holds the reins of power?

It can be inferred that genes are not solely responsible for stress; rather, the brain assumes a significant role. However, before attributing all responsibility to the brain, it’s important to pause and consider other contributing factors. What might those be?

Indeed, external factors play a pivotal role in shaping the stress we encounter. What exactly constitutes this process?

The hypothalamus, a gland in the brain overseeing the hormone system, dispatches signals directing the pituitary gland to release hormones prompting the adrenal glands to produce and release cortisol. This signaling process is guided by commands from the conscious region of the brain, which assimilates information from the external environment. Thus, stress emerges as an involuntary and unconscious response. This implies that external influences wield influence by transmitting signals to the brain, which in turn processes them into stress mechanisms.

However, some individuals confronted with the same issue exhibit varying bodily responses. Why is this the case? The reason lies in the unique production, regulation, and reaction to cortisol in each person. Due to individual differences in backgrounds, each person possesses distinct processes and coping mechanisms when facing stressful situations.

When an individual’s brain responds to psychological stress, it triggers the release of cortisol, which subsequently inhibits immune system reactivity. Consequently, when the body encounters a virus during a period of psychological “inactivity” or normalcy, where the virus might not have posed a significant threat, the disrupted immune system becomes overwhelmed, potentially allowing the virus to proliferate. The resulting physical symptoms stem from the initial psychological cause. This underscores the precedence of psychological factors over physical ones in shaping health outcomes.

The field that explores this theory is known as Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI), which investigates the interconnections between immunity, the endocrine system, and the central and peripheral nervous systems. One example is the correlation between stress and various diseases; individuals experiencing prolonged stress may develop digestive disorders. Another illustration involves children frequently exposed to parental conflicts, rendering them more susceptible to viral infections.

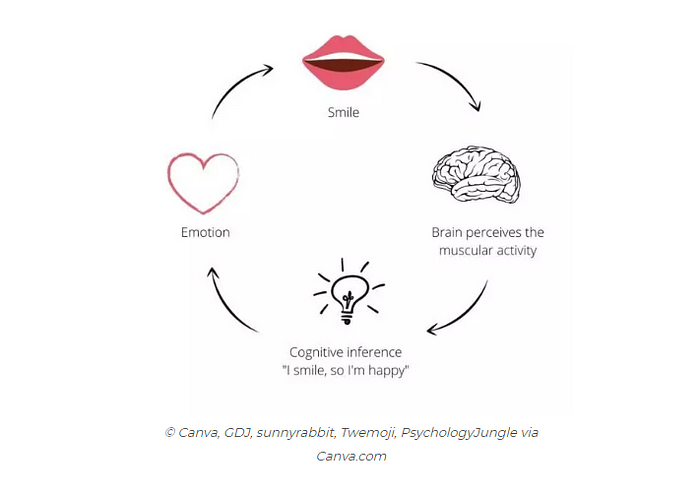

Hence, it is paramount to cultivate positive and contented thoughts when navigating life’s challenges. A simple yet impactful action is to intentionally smile, as this gesture can stimulate activity in the “happiness center” of the brain. This underscores the notion that our behavior can regulate our bodily functions, ultimately influencing the expression of our genes. In this way, the mind directs the body, which in turn influences the genome.

Indeed, our biology is influenced by our behavior, underscoring the significance of emotional intelligence. This awareness enables us to regulate our responses to external events beyond our control.

It should be noted that our thoughts play a pivotal role in determining how our genes are expressed!

References:

Boyman, O. and Sprent, J., 2012. The role of interleukin-2 during homeostasis and activation of the immune system. Nature Reviews Immunology, 12(3), pp.180–190.

Meszaros, K. and Patocs, A., 2020. Glucocorticoids influencing Wnt/β-catenin pathway; multiple sites, heterogeneous effects. Molecules, 25(7), p.1489.

Ridley, M. (1999). Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters. Harper Perennial.

Souza-Talarico, J.N.D., Marin, M.F., Sindi, S. and Lupien, S.J., 2011. Effects of stress hormones on the brain and cognition: Evidence from normal to pathological aging. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 5, pp.8–16.